Women and people of color have been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic fallout. The pandemic is exacerbating existing inequalities—particularly racial inequalities—in terms of employment, financial security, and health access and outcomes. Economic repercussions have fallen disproportionately on women. Sectors that employ large shares of women have been hit especially hard by the pandemic, and disruptions to daycares and schools have left mothers shouldering greater childcare responsibilities—at the expense of their careers.

In this brief, we analyze whether this deepening of racial and gender inequalities holds true of eviction risk as well. In previous work, we have demonstrated that landlords file for eviction against Black and Latinx renters—especially Black and Latinx women—at higher rates than against their white and male counterparts. The share of Black tenants receiving eviction filings is often far larger than their share of the renter population. Between 2012 and 2016, nearly one in every four Black renters lived in a county in which the Black eviction rate was more than double the white eviction rate. Black and Latinx women were also evicted in much higher numbers than Black and Latinx men.

To analyze how the pandemic may be changing who faces the threat of eviction, we draw on data collected through the Eviction Tracking System (ETS). The ETS collects the records of eviction filings—the first step of the eviction process recorded by the civil courts—across sixteen cities and six full states. In each of these areas we also have equivalent historical eviction filing records.1

Eviction filings do not identify the race or gender of tenants who are facing removal. As such, we use well-validated statistical techniques to impute, on the basis of names and addresses listed on the court records, defendants’ race/ethnicity and gender.2 We do this for both historical data and for records collected since March 15th of this year, which allows us to compare patterns before and during the pandemic.3

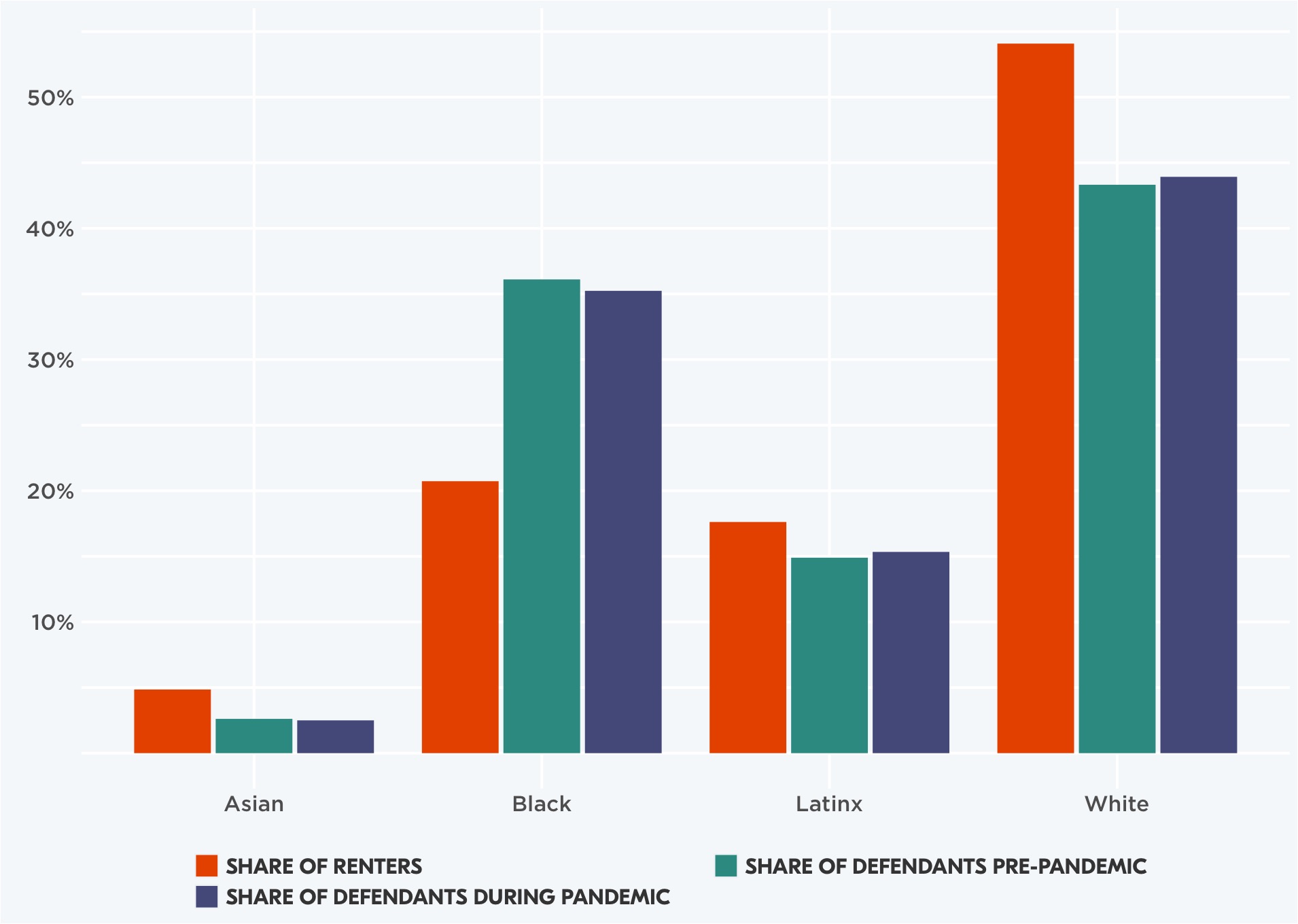

In Figure 1 we plot the share of eviction filings against Asian, Black, Latinx, and white individuals before and during the pandemic, as well as the share of all renters in those racial/ethnic groups. Prior to the pandemic, Black renters received a disproportionate share of all eviction filings: they made up 21% of all renters in ETS sites, but received 36% of eviction filings. They continue to be over-represented during the pandemic, receiving 35% of filings since March 15th. Asian, Latinx, and white renters were under-represented in eviction filings relative to their share of the renting population in pre-pandemic times. This remains true during the pandemic as well, although the share of filings against Latinx and white renters has increased slightly. For example, the share of filings against white individuals has increased from 43.3% to 43.9%, still well below their share of the renting population in this sample (54.1%).

Note: Share of renters by race drawn from the American Community Survey

The changes we observe in Figure 1 between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods represent a weighted average across all ETS sites. What’s true of Houston, however, may not hold in Cincinnati. When we examined these patterns in each of the sites separately, a few stood out.

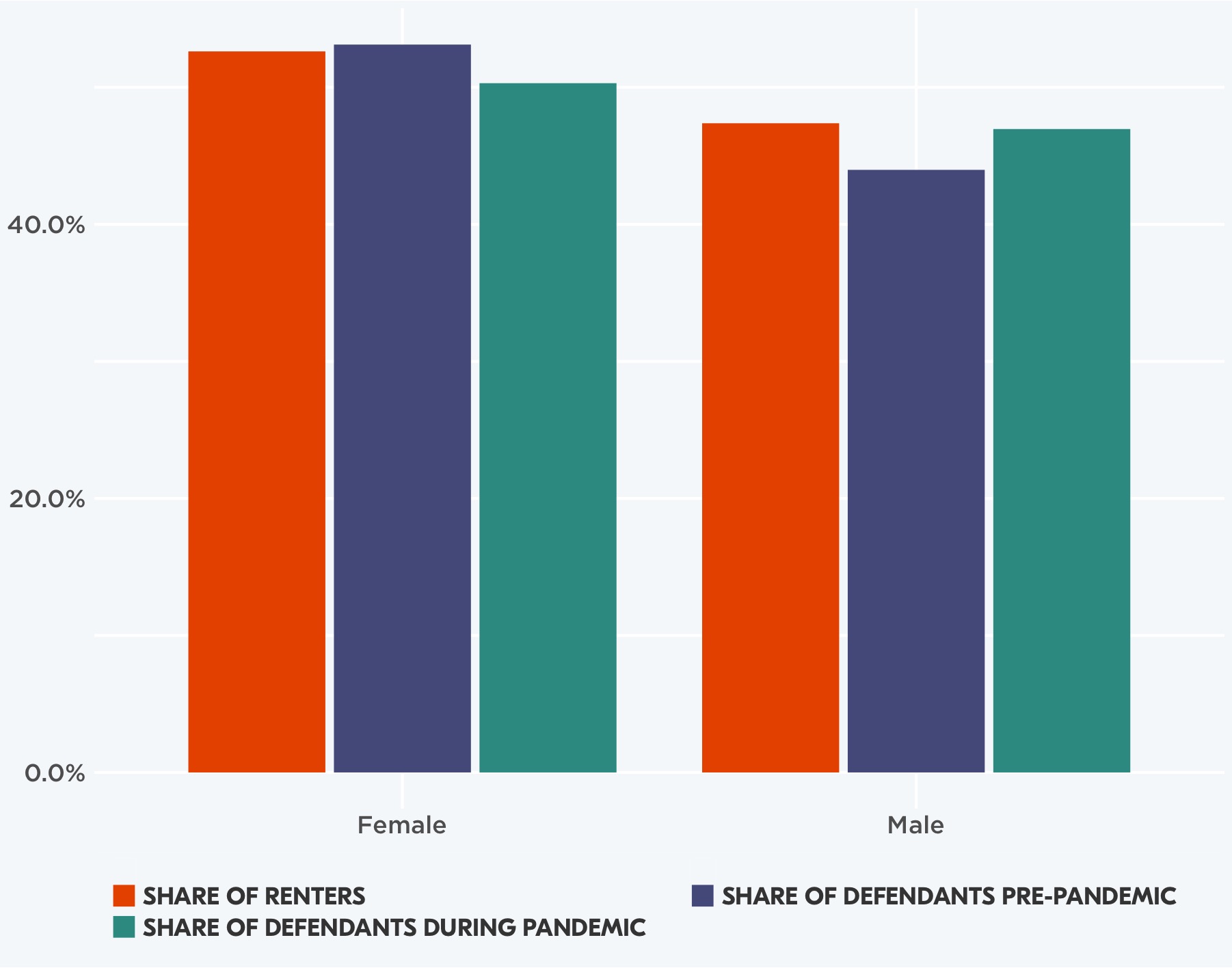

The majority of eviction filings are against women. In a typical pre-pandemic year, 54.7% of individuals filed against for eviction in our sample were women. Since the pandemic began, much the same has held true: 51.7% of individuals filed against for eviction since March 15th have been women (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 shows a narrowing of gender disparities in filing patterns during the pandemic. This has played out to a greater degree for some racial/ethnic groups than for others.

Understanding the demographics of those currently facing eviction filings is critical in a complete analysis of the broad social harms of the COVID-19 pandemic. It also provides policymakers with a roadmap for interventions designed to ensure that eviction protections serve not only to protect renters, but to reduce inequalities that are introduced or exacerbated by the pandemic.

Our analyses suggest that eviction filings over the last eight months have, by and large, targeted the same communities and individuals who were at risk of eviction prior to the pandemic. While fewer cases than normal have been filed over this period, the populations at risk of eviction have not substantially changed. Rather, the threat of eviction is concentrated among those for whom displacement was an all-too-common risk before the pandemic began.