Disparities in health at birth expose fissures in the American dream. The conditions of a child’s gestation and birth—social and environmental conditions over which they have no control—help or hinder a child’s ability to grow and flourish. Birth outcomes impact a person’s health and wellbeing across their lifetime, as well as multiple generations within families and communities.

In a March 1st JAMA Pediatrics journal article, we examine how evictions impact birth weight, prematurity, and infant mortality. We find that infants born to mothers who have an eviction filed against them during their pregnancy are more likely to be born prematurely or low birth weight, and may also have higher mortality compared to infants born to mothers evicted at times other than pregnancy. In other words, in utero subjection to eviction harms infant health and development.

Public health researchers have long investigated how adversity such as stress and poverty during pregnancy affects infant and child well being, including via:

We suspect that eviction is another form of adversity affecting infant health in similar ways. The worry of not knowing whether a person can keep a roof over their heads or how to afford food, especially while pregnant, adds to challenges women already face in the United States.

Eviction is a common, traumatic experience that may affect the health of both mothers and children through multiple pathways. Rising rents, stagnant wages, discrimination in housing, and other structural factors subject mothers to inescapable hardship. These maternal disadvantages affect the health of children and families, too, creating intergenerational chains of structural harm.

More than six percent of U.S. renter households experienced an eviction filing in 2016, a year when over 3 million eviction cases were filed despite a low unemployment rate under five percent. Eviction has also been linked to a wide range of other adverse health effects ranging from risk of hospitalization in childhood, to death from any cause across the entire lifespan. Previous studies, though, have not investigated the individual level link between eviction and birth outcomes.

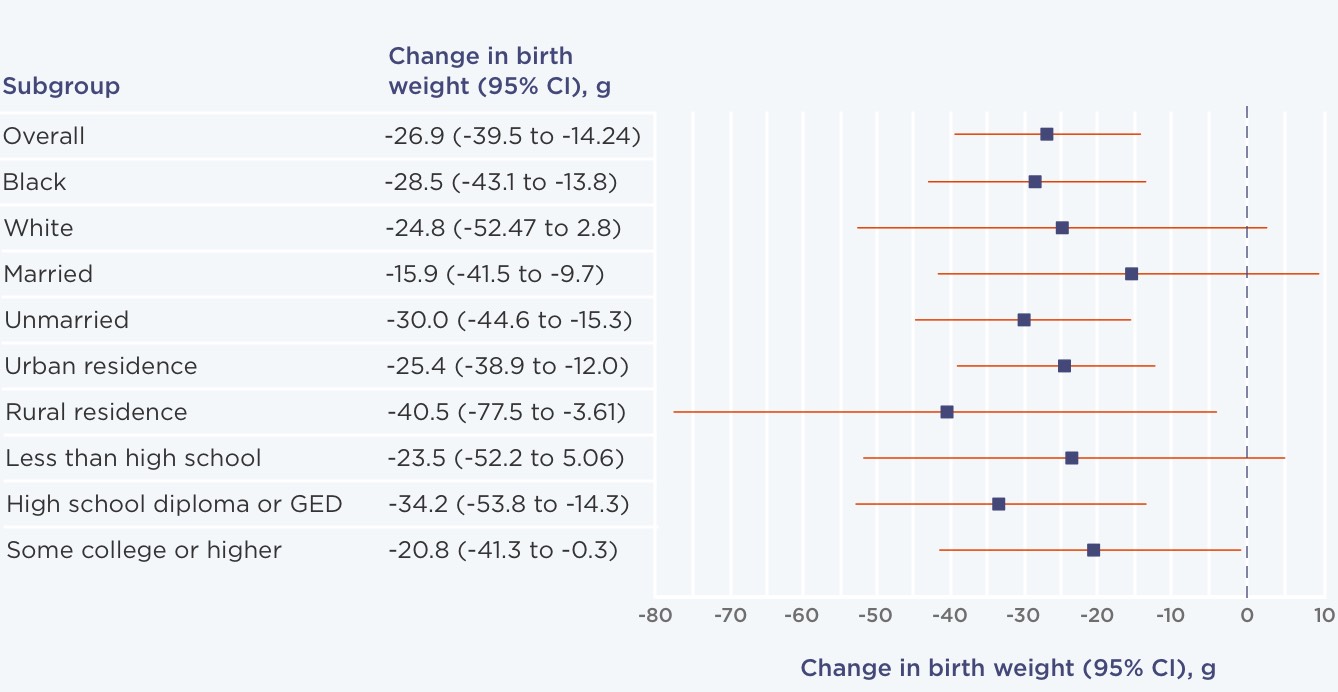

Data are from court records and birth certificates in Georgia from 2000 to 2016. GED indicates General Educational Development.

These findings are remarkably consistent across demographic groups. Women who are evicted during pregnancy have different birth outcomes than women who experience eviction at another point in time. Decreases in infant birth weight are even evident when we compare births outcomes for the same mother. In other words, children who share the same biological mother and experienced an eviction in utero have lower birth weights on average than siblings who didn’t have that experience, making it unlikely that worsening health outcomes are due to some other factor.

Every human being needs a safe and secure place to call home, and the results of this paper speak to the outsized impact of housing policy on individual, family, and community health. And yet, eviction rates remain high across the United States despite a federal eviction moratorium. In 2021, we are at a place in U.S. history when more people are unemployed and have lost health care than ever before through no fault of their own.

The eviction burden is felt particularly acutely by Black and Latinx women. The Eviction Lab estimates that landlords filed more than 61 million eviction cases between 2000 and 2016. Policy interventions to make evictions costly and rare rather than cheap and common have the potential to not only mitigate the housing crisis, but to improve the long term and intergenerational health outcomes of renters, Black, Indigenous, and communities of color, and their children at risk of eviction.